Spend any time doing genealogy and you’ll run into this problem: too many men of the same or similar names in the same place. Men not in the place they are supposed to be, or when they are suppose to be. The inclination is to skip the mess and move on to other things, but there comes a time when you must sort it out.

For me, that time when it must be sorted out came when, as a DAR Lineage Research genealogist, a member came looking to prove her lineage to a man who would be a new patriot. The DAR has specific requirements for proving new patriot ancestors. First you must be able to document the service of that individual. Next you will need to prove that your ancestor resided in the place where service was rendered. There are exceptions but never mind for now. Then of course, you need to document the major milestones of their life, and that is birth and death dates and locations, marriage records to document the wife’s name change, and of course the connection between generations to a daughter or son. And yes, it’s a precise process and your submitted application and supporting documentation will be examined. Closely. At National Headquarters in Washington, D.C. by a seasoned professional genealogist. If your application can pass muster, you can take it to the bank.

This case will be posted in multiple parts just because it’s so long and complicated. So, simply put, here’s our job ahead.

Establishing the documentation necessary to prove a New Patriot, Charles Karl Joseph (?) Geissinger/ Kissinger by lineal descent through his daughter, Catherine Geissinger Mower

In order to have a foundation for establishing this New Patriot, we must prove:

1. Service of Charles Karl Joseph Geissinger/ Kissinger,

2 Residence of same, at time of service.

3 Connection to daughter, Catherine Geissinger Mower.

Just three things. Simple, right? It often isn’t. First thing is this guy’s name. It seems to change everywhere he goes and that’s not a good sign, nor is it at all helpful to the researcher. Here’s a chronology taken from a compiled biography found on Ancestry. (Will not include the usual commentary about taking unverified documents from Ancestry, but just know that in parts it looked credible.) Note the name changes and the locations. If I was unable to verify any of this, it’s noted.

Chronology

15 Oct 1766, ships list as Carl Geissinger, arrival to port of Philadelphia.

11 Jul 1767, listed as a run-away indentured servant as Charles Geisinger, Alloway Creek NJ.

9 May 1768, listed again as a run-away servant as Charles Geisinger, Salem County NJ.

9 Jun 1776, Karl Gysinger taken prisoner at Battle of Trois Rivieres in Canada. (Not found.)

16 Mar 1777, Charles Geisinger, in Nicholas Von Ottendorff’s company. Source: PA Archives, Series 2, Vol XI, pg 88. “Continental Line, The German Regiment, July 12 1776 – January 1, 1781.” Fold3. Note: No location given.

1790 Census, listed as Charles Geissinger in Frederick MD.

9 Aug 1794, Charles and Catherine Geissin in baptismal record in Adams County PA.

1800 Census, Charles Geisinger listed in Frederick County MD. District 3.

28 March 1805, Bounty Land Warrant #202-1900 issues to Charles Kissinger of Colerain Twp., PA.

1807, 1808, 1809, 1810 Examination of List of Taxable Inhabitants, Charles Gisinger or various spellings, Colerain Twp., Bedford Co., PA. No records of any type found.

Note: No will is found for in Bedford County PA under any spelling.

So what do we have here? Let’s look at his name. His first name might be Charles or Karl/Carl. Or Charles Karl, or Karl Charles. There are so many variations in the surname it’s hard to know where to start! The man who landed in Philadelphia 1766 could easily be the same indentured servant who went missing in 1767 and 1768. A quick check of given names and nicknames, always helpful, shows that Carl is a nickname for Charles. So anytime we see Charles or Carl, or even Karl, we can proceed knowing that they might be the same person.

The variations in surname are a larger issue. As we go, we’ll look for patterns and degrees of variation. However, it’s going to be a big stretch from Geissin in Frederick MD to Kissinger to Kissinger in Colerain Twp. PA.

Now let’s look at the statement in the family biography that he was at the Battle of Trois Rivieres in Canada and was taken prisoner on 9 June 1776. While the main battle was fought on 8 June, it could easily be that Charles Carl was captured the next day. That is, if he was there. My first thought is to question how he got from New Jersey to Quebec. He might have decided somewhere along the way that the military was the best career for him and signed up with the Continental Army. It would have been reasonable for a unit to travel all the way from New Jersey to Canada, on foot. And Brigadier General William Thompson did come from Pennsylvania and had joined up after hearing the news of the Battle of Bunker Hill. After an extensive search no company records, enlistments, nor pay vouchers for units in this campaign have been found, so we can’t use this. Pity.

As a side note but of utmost importance here is that the DAR only accepts military service between the dates 19 April 1775 and 26 November 1783. Other types of service are also recognized but that’s a whole other blog post or two. Therefore, what we need is military service between those dates, if we are going to claim military service. (Seen a Dar member to find out about the DAR’s Genealogy Guidelines and more information about qualifying service.) Bottom line: we need service between those dates.

Take away:

1. If other researchers have gone before you, gather all of their work that you can find. Examine it closely, of course. Break it down into individual elements. Try to find sources for each of those elements.

2. Names are the game, especially in this case. Consider nicknames for given names and say the surname out loud to find variations. Take note of any names that don’t fit, especially if the locations had changed.

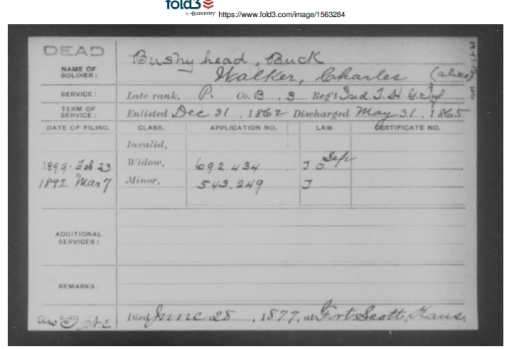

4. When dealing with military service, the first stop should be Fold3. First, search under all name variation just to be sure. Next, if you have any clues about the unit he served in, search for unit records. Then search for records by state he lived in.

Next time: Does any of this make sense?

Take away:

Take away: